It's 5:23 AM, Monday, October 18th, 2010. I'm seeing this on the display of my phone wondering why I'm awake when my alarm isn't set to go off for another seven minutes. This has been happening to me a lot lately. I get up and gather the few possessions that I need for the day that I've left all together so as not to have to scramble around the room and risk waking my wife who is probably at minimum partially awake despite my best efforts to the contrary. Downstairs, I put on my work uniform for somewhere around the 220th time. I'm buttoning up the literal, not figurative, blue-collar shirt and I have to let out a little laugh as I come to realize the expansive degree of separation between the profession in which I find myself today and the ones in which I was associating myself with during the weekend prior.

The Friday and Saturday before were two very long days for me as I attended a conference at Drury University entitled "Subverting the Norm: The Emerging Church, Postmodernism, & the Future of Christianity". I didn't count heads or anything, but I figured around 250 people attended the conference for at least part of it, although I doubt that there was ever more than 200 people present at one time. Those in attendance fell almost exclusively into one of two categories: theology scholars or church practitioners. Some were both. I'm sure there were exceptions, but none that I met. Everyone I spoke to either came right out of the gate asking me about my educational background or they first assumed I was a student and then, upon finding out that I wasn't, asked me about my educational background. During one of the sessions that I sat in on hosted by Chris Rodkey titled "Satan in the Suburbs: Ordination as Insubordination", Mr. Rodkey suggested since we were only a small group of about eight that we go around the circle and introduce ourselves. I was second in line and merely said, "Hi, my name is Levi and I'm from right here in Springfield, Missouri." I left it at that despite the continuing eye contact I was receiving from Mr. Rodkey who was, no doubt, encouraging me to share more about myself. But, I just politely held his gaze with a smile to let him know that I had no intention of describing myself any further. After several seconds, he moved on to the next person who without hesitation or pause listed his own currently held titles, the degrees he had and were still studying for, and a couple other qualifications that he must have deemed relevant to the conversation and necessary to be mentioned. The gracefulness and almost sing-song quality in which this information was delivered suggested that these verses of self-qualification had been recited to people many times.

That last observation maybe sounded a bit like I am bothered by being surrounded by academics or that I am in some way demeaning someone for their post-high school education and achieved titles. However, rather than delete the sentences and try again in my defense, let me instead just state that I'm merely attempting to paint a picture as to what sort of people I was attending a conference with while also pointing out that stating one's titles and educational background as a means to introducing yourself was not only done but also encouraged by the hosts. This follows right along the social norm here in the West where it is commonplace to identify oneself with one's occupation. I could write an entire blog about my psychoanalysis on this alone, but instead I'll just say without further explanation that this phenomenon of occupation as a means to self-identity is simply our attempt to feel purpose in our lives. But, as a result, since different occupations have varying degrees of levels of their contribution to society, at least in the eyes of society, people consequently are made to feel that they are only as useful, only as important as their respective occupation relates to the general consensus' view of it's role in contributing to the general welfare of society. In layman's terms, the hosts at this conference advocated, whether purposefully or not, the old phrase 'you are what you do.'

There's entirely too much to go over about what I disagreed with at this conference without writing a book about it. Which, who knows, maybe I will do eventually. But, I will say that of all the names of writers, theologians, scholars, and the like being thrown around that weekend, none did I hear so often than those of Jacques Derrida, Thomas Altizer, and John Caputo (who was one of the keynote speakers at the conference). One name I didn't hear save for a few times was that of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Nietzsche's writings, I will say with much conviction, is the launch point of the entire movement in which the conference was being held. Nietzsche's statement, "God is dead", brought into mainstream media by TIME magazine, ushered in a new theology most commonly referred to as 'Death of God Theology.' There was much talk about this theology throughout the entire conference, so much in fact, that at one point I jokingly wondered if I hadn't stumbled into the wrong conference altogether. At the time, I was unaware of what this theology even was and only had a vague understanding, at best, of what Nietzsche had written about all those years ago.

I still have loads of research to do before I can come to any solid conclusions or theories of my own, however in good scientific form I will throw out my hypothesis on the table: Postmodernistic thought was born not out of a study of the Word of God and documented history, but rather came out of a self-negating philosophy that sought self-justification. The emergent church (and most 'emerging' churches, as well) are simply the ecclesiological practices of this theology which may be better defined as atheology. To put it simply, the only thing that I can see that separates these people from atheists is that they claim that there is a God, but they completely and radically redefine what God is into something unknowable. And, thus, create their own God based out of their own desires and cultural standpoint.

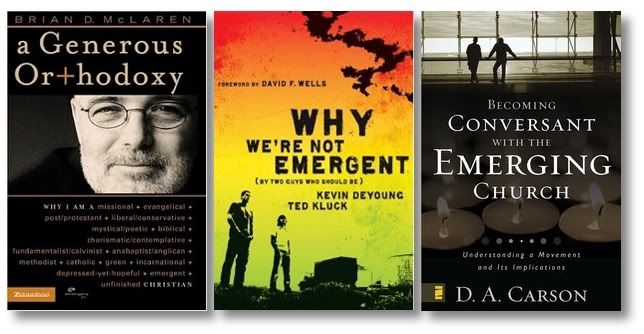

Like I said, I won't go into why I believe this hypothesis to be true because I haven't done all the intended research yet and right now I'm only basing this on my own observations. But, for good measure I have opened the door here to any critics (as well as anyone else) to contribute to the ongoing conversation that I am having here. I have no "formal education" that gives me some status, official knowledge level, or title. I just read and research those subjects that I feel God gives me a passion for. So far, in direct relevance to the subject at hand, I have attended the conference that I spoke of here in this blog, a book study on A Generous Orthodoxy by Brian McLaren, and have read the following books:

- A Generous Orthodoxy by Brian McLaren

- Why We're Not Emergent (By Two Guys Who Should Be) by Kevin DeYoung & Ted Kluck

- Becoming Conversant With The Emerging Church by D.A. Carson

3 comments:

Hi, Levi. I was with you in the breakout session that Chris Rodkey hosted. I suppose I fall into the "both" category, since I spend more of my time doing organizing, training, and outreach for Christian Circles (a type of house church) than doing theological writing and I'm not paid for doing either of these things. I'm bivocational - I write grants and perform research evaluations for social service agencies for a living. I don't believe I mentioned that when we were introducing ourselves, so your assumption that these introductions were about what we do for a living was incorrect in at least one case. Having been there myself, however, I can see how one might arrive at that conclusion.

I think your initial impression of postmodernistic theology is not quite right. First, it's important to understand that the notion of the "death of God" is a development of Philippians 2: 5-11 and the incarnation, Martin Luther's theology of the cross, and Hegel's interpretation of the last two.

This theology is also radically iconoclastic, and so would completely reject the notion of worshiping a God we invent. This is precisely the God that this movement rejects - in the interests of embracing the Otherness that doesn't go away when we stop believing our own wish fulfillment fantasies.

Far from embracing the God of Greek philosophy - the God of Aristotle - and rejecting the God of the Bible, this movement maintains that it is the latter and not the former that remains when our own wish fulfillment fantasies are subtracted. Biblical literalism is rejected, in other words, but the Bible remains the source text for this theology, with a critical eye cast toward the Western philosophical tradition.

Hey, Alan. Glad you found me on here. Thanks for your comment.

To clarify, in regards to the introductions I spoke of and their suggested intent, I didn't mean that they were simply what we do for a living as you interpreted it. I meant that they were an encouraged opportunity to spill what we do and know (whether compensated or not.) My only point was that, save for a pastor from Portland, every conversation I entered into at the conference didn't last 30 seconds before I was asked about my education or involvement in an institution. Even this breakout session included the encouragement to tell about myself. However, I no more thought that my acquired titles were of any importance to the conversation than I thought my favorite color was relevant and therefore decided not to share anything more than my name and hometown.

About postmodernism, my impression can neither be right nor wrong, right? (pun, intended) It's only what I have gleaned from my exposure of discussion on the subject.

Concerning that, however, I would argue that "Death of God" is a development resulting from tunnel vision of biblical text, rejection of the biblical context, misinterpretation of Luther's intent, mixed well with two-thirds cup self-serving liberal agenda.

However, I still haven't done all the intended research, so my opinion isn't rock solid or anything. Then again, nobody's really is.

What do you mean by the "Otherness"?

One of my students pointed me to your blog.

I didn't mean to make anyone uncomfortable by the introductions of my talk, but I am pretty sure I asked everyone to mention their denominational affiliation and theological education, if any. And I did this intentionally because the topic of the presentation was about exposing the flawed fissures of how vocation, discernment, theological education, and ordination processes are practiced in mainline denominations.

As it happens, I thought that one of the great things about that conference was that there were a lot of academics and church workers there, and some students, and some interested laypeople, and I was excited to know who people were and where they were coming from, since this was a unique situation. Whether it worked for everyone is another question.

Post a Comment